The great British violinist, Ralph Holmes, died 30 years ago this year. I studied with him from the age of 12, and my last lesson with him was a few months before we lost him. I was 17, and just about to go to the Royal Academy as a ‘grown up’. To the Academy’s irritation (understandable, I suppose), I refused to have a teacher for the first few months. I had the sense that, whilst I had been having these astonishing lessons for years, I had not had the good sense to really listen, to take on board what was being said to me. So I spend the time going back over the works that I had studied with Ralph, and some that I had not . Jeanette Holmes gave me access to his marked materials, and I studied some new works with him, such as the Hamilton Harty concerto, in those months. It was years before I met a teacher who would have such an impact. If I am truthful, it was not until I went to Louis Krasner that I found what I remembered from this extraordinary musician and friend.

The opening of Jeremy Dale Roberts’ ‘Capriccio’. with my notations of today’s work with the Holmes performance

However, Jeremy Dale Roberts has enabled me to go back to that excitement and inspiration. I am preparing Jeremy’s ‘Capriccio’ for a concert at Kettles Yard on the 27th of this month (with Roderick Chadwick). This piece was written for Yfrah Neamann. However, Jeremy had, many times, whispered to me that the recording which Holmes made of it was extraordinary. Jeremy and I have never really talked about this violinist, but it has always been clear to me that he made a profound impact on this great composer. Today, Jeremy sent me Holmes’ recording, with the pianist Ronald Lumsden The card which Jeremy sent with the recording refers to Ralph:

‘…like the Young Apollo or one of Blake’s Angels’

I listened and realised that this was a great opportunity for me, as part of the work on Jeremy’s piece, to have a lesson. I spend a lot of time doing this with other players who are lost to me, David, Joachim, Bull. So really, this is more logical. So I have just spent a couple of hours, violin in hand, listening, playing and thinking. It has been to put it mildly, a revelation. Here it is:

Jeremy Dale Roberts-‘Capriccio’ 1965 Ralph Holmes (Stradivari 1734), Ronald Lumsden-Piano

Specific observations, which formed the meat of today’s lesson:

Opening: Echoes of Stravinsky’s ‘Duo Concertant’. Incorporation of Left hand pizzicato into the tremolo-as one colour. Immediate shaping of the passage work, responding to Roberts’ ‘flessibile’, as a living organism. No display! Note that, Peter. The capricious nature is there, constantly, in the balance of rubato forward and backwards, the use of silence. Holmes harmonics are always ‘open’ in sound, and he allows humanity in the way material falls silent, runs out of breath/bow. I was reminded, in the ascending passage at 22″ of him teaching me the Beethoven Concerto, his love of finding ways in high passage work, of making the fingers push each other out of the way, avoiding merely digital playing.

44″‘: This is marked ‘Loure’. and initially, I was not sure of what JDR wanted. Holmes plays the incarnations of this figure, here, at 2’08” (Augmented), 3’45”, and the end, dreaming. Each one is a development of the previous (there’s an effortless teleological view in the playing). The first manifestations are hesitando, separated, then, gradually, more joined, eventually, by the end, glowing.

46″: The singing passagework. This is birdsong, not virtuosity, and the various characters always shine through, like the Szymanowski-like emphasis of the appogiature, which are wonderful. As thsi section builds, I love the various weightings of vibrato, and the heft which Holmes allows into the bow arm, but never violence. The long melody, beginning on the G string, which rises and falls to 2’14”, is a testament to right hand eloquence, and Holmes’ vibrato response to Roberts’ ‘con fervore’. He kept so much of the finger pad in contact with the string, which released this unmistakably human sound. At this point in the piece, Holmes is restraining, even repressing, ‘portamenti’. There’s a pay-off for this, later.

4’40: Something amazing. Holmes releases the intimacy of the ‘Poco meno mosso’ passage which he has just played, and the increasingly human quiver in the vibrato, (Eliot’s ‘circulation of the lymph’?), with a wonderful ‘glissando armoniques’ (as Jolivet named it in ‘Pour que l’Image Devienne Symbole’). This sets up the high G flageolet, with the sublests pre-echo of natural harmoniques glinting on the way up.

8’16”: Here’s the reward for all the restraint which the performers have shown up to now. Jeremy has marked ‘declamado’ and Ralph releases, at this unmistakable climax, a wonderful range of downwards ‘portamenti’. And they remain, to the end of the piece. Now that the voice has been released, it can sing free, unfettered.

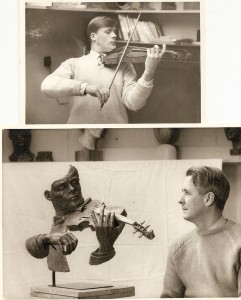

Ralph Holmes in 1962, in his twenties, and a sculpture made that year by the inventor/sculptor Lewen Tugwell

And here are some general things, as they came to me. They are mainly, admonishments to myself: reminders to avoid falling into bad habits.

PSS on RH 5 4 14

-Ralph’s ‘passage work’ is never merely brilliant, superficial, but always human. Everything is vocal.

-Singing, always human, always fallible.

-Ralph always told me to find as much of my expression as possible in the Right Hand, not just the left. This recording is an object lesson in that.

-This is a rhetoric which makes amazing use of emphasis, of caesurae, of weight

-Ralph’s eloquence is so much rooted in an astonishing command of the open, warm parts of the alphabet, in vowels. He never makes the mistake, so common in string playing today, of going for the easy effect by overuse of splashy consonants

-This playing seems to look for the reason behind every colour, timbre and gesture, and, kindly, without intrusion, bring that to the fore

-Portamenti are relatively rare, but when used, released, if you like, have real power

-The E string sound is always warm, covered even. How does he do it?

Technical Notes

Holmes’ playing, technically, was a fascinating synthesis of European and American approaches. As a young man, he studied under David Martin, which put him firmly in the line of influence from Rowsby Woof. However, there was a major change in his approach, in his twenties, which resulted from a brief period of study with Ivan Galamian in New York. Holmes should never be descrined as a Galamian disciple; indeed, from the very first moments that I met him as a 12 year old, he was open with me about the limitations of Galamian’s school, from a musical point of view. However, after his return from study in the US, he found a way, uniquely his own, to incorporate Galamian’s approach to the right hand into his own technique, freeing it up. I do remember that he was round to supper at my parents house in April 1981, and was very clear about the demarcation between his violinistic approach and the Galamian players. This stuck in my memory (I was 14 at the time) because next morning Galamian’s death was announced. The photo of him playing above, shows his right hand in the pre-Galamian state. When I studied him, he demonstrated and used a much more energised, ‘spread’ approach to the hand.

Holmes’ right hand as I knew it. The Violin is the Habeneck Strad, and the bow, by Stephen Bristow-Ralph bought two spectacular examples after I bought my first on by this maker, when I was 13

An important factor in the lyrical approach that can be heard here, was Holmes’ ‘open hand’ approach to fingering. Put simply, he sought to keep the left hand in ‘extended’, reaching configuration as much as possible, in the quest for the most singing line. I was lucky enough to study a number of works which enabled me to see him explain this in great detail. These include the Prokofiev ‘Five Melodies’, the Britten ‘Lullaby’, and the Chausson Poème. It’s worth mentioning that a result of this was (and I confess that we disagreed about this a lot in lessons) that he always sought to avoid the 4th finger for expressive high points. I was not the most compliant teenager, and made now secret of the fact that I sensed that my hand was developing a different way; which it did!

First result

One of our rehearsals for Capriccio. .24 4 14 London

Peter Sheppard Skaerved-Violin, Roderick Chadwick-Piano

Posted on April 5th, 2014 by Peter Sheppard Skaerved